When "It Depends"

- Brian Fleming Ed.D

- Jun 9, 2025

- 8 min read

How to Turn Uncertainty into Your Superpower

You're in a meeting when someone asks the question you've been dreading: "Are you certain about that?"

Maybe it's your board chair leaning forward: "So you're certain enrollment will keep dropping?" Or the provost during budget planning: "How many students should we plan for next year?" Or a dean pushing for answers: "Are you sure this new program is going to work?"

You feel that familiar knot in your stomach—the need to sound like you've got it all figured out. Everyone wants a clear yes or no, something definitive they can act on.

But 99% of the time, if you're being honest, the real answer is, "It depends." Because you don't have a crystal ball. You can't predict the future. And these kinds of issues are often really, really complicated.

But you can't always say that, can you?

It feels like waving a white flag. Weak. Indecisive. Evasive. Too "academic."

So you cave. You blurt out an answer, usually the first one that comes to mind. And suddenly, you've turned an otherwise complicated issue into something everyone can get behind.

But it's not the right answer, and you know it. Because—well, "it depends" on so many things being true, so many factors, so many variables you can't control.

After You Answer The Question…

You spend the next few months—or years—hoping you got it right but knowing deep down that you're about to be proven wrong any day. But the bigger problem, as I see it, is that none of this is usually your fault. You're not trying to deceive anyone. You haven't built your career on lying to people.

Plus, higher education rewards certainty. It's a knowledge industry after all, fueled by answers. Certainty is how you got to where you are right now in the first place.

Scenarios Over Certainty

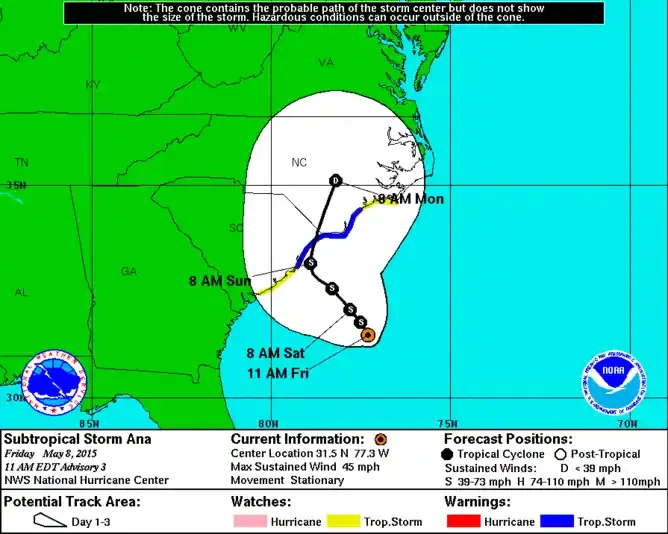

Max Mayfield spent decades as director of the National Hurricane Center, an organization built for certainty, made up of brilliant people making life-or-death decisions about what to do when hit by big, catastrophic storms. You know, the notices that come telling people to shelter in place or evacuate. That was Mayfield's responsibility, and he was really good at it. But not until he abandoned certainty and embraced scenario planning.

It started with analyzing data models. Over and over, Mayfield watched as people would stare at a model and obsess over one detail—a thin black line showing where the hurricane was supposed to go. You know the picture.

That line represents the computer's best guess about where the storm's center will travel. It's calculated using dozens of variables: wind patterns at different altitudes, ocean temperatures, high and low pressure systems, the storm's current speed and direction, even the time of year and what similar storms have done in the past. Supercomputers crunch all this data and spit out a path—the famous skinny black line.

But here's the thing: it's still just a guess. The best guess meteorologists can make at the time, but in the end it's still just a guess.

What people ignored, Mayfield came to believe, was the big white cone around that line. Meteorologists would include what's called a "cone of uncertainty" to show all the places the storm might actually end up. But few paid attention to it because it was vague and full of uncertainty.

In fact, the National Hurricane Center generally found that everyone hated the cone. The public didn't know what to make of it. Politicians complained about it being too vague. Emergency managers found it frustrating to deploy resources across such a wide range of possibilities.

Everyone wanted the line. They wanted certainty—will it hit me or not? Which frustrated Mayfield because the line was not always accurate and his job was to prevent deaths and destruction. Sometimes the line was just plain wrong.

Mayfield got so frustrated with this pattern that he built his career on reminding everyone: "Don't pay attention to the skinny black line." It became his signature message.

He wasn't being provocative. He was trying to save lives by getting people to recognize the inevitable uncertainty that comes with a storm and prepare for that uncertainty instead of betting everything on one prediction.

Practicing "Appropriate Uncertainty”

Philip Tetlock spent decades studying what makes some people better at predicting the future than others. His research, involving thousands of forecasters making tens of thousands of predictions, revealed something surprising: the most accurate predictors weren't the confident experts with the strongest opinions. They were the people comfortable saying "I don't know" and thinking in ranges rather than certainties.

Tetlock calls this practice "appropriate uncertainty"—matching your confidence to the actual predictability of the situation. The best forecasters know when to be humble about what they can't control, and they hone this practice over time.

Keep that in mind as we consider what's happening in and around higher education right now.

Take demographic decline, or the enrollment cliff. This one feels unavoidable. Demographers predict a 13-15% decline in traditional college-age students between 2025 and 2029, concentrated in regions where many institutions depend on local enrollment—New England, the rust belt, rural communities across the south. The skinny black line is stark: fewer 18-year-olds means fewer students, period. But the cone of uncertainty around that prediction tells a different story.

But what if the real answer to the demographic cliff is—well, it depends. How catastrophic it might be for your institution depends on so many variables. It depends on whether families start making different choices about college. It depends on whether more students decide to work for a year or two before school, building up demand that hits later. It depends on whether remote work means students can live anywhere, suddenly making you compete nationally instead of just locally. It depends on whether online education gets so good that geography stops mattering entirely. It depends on whether tight budgets make families choose the affordable school down the road over the expensive one three states away. It depends on whether new immigration policies bring in more college-age students than anyone expects.

Smart leaders are building capacity that works whether they get fewer traditional students, different types of students, or students showing up at completely different life stages.

Same with technology. The skinny black line says AI will steadily transform both learning and employment, creating predictable disruption that institutions can plan for over the next five to ten years. Everyone's building strategies around this assumption right now.

But appropriate uncertainty means acknowledging that predicting technology adoption rates is complicated, to say the least. How disruptive AI will actually be depends on so many unknowns. It depends on whether AI capabilities advance so fast that entire degree programs become obsolete within two years instead of ten. It depends on whether regulatory backlash slows AI integration to a crawl, giving traditional approaches more staying power than anyone expects. It depends on whether students reject AI-heavy learning environments and demand more human interaction. It depends on whether cyberattacks become so common that institutions retreat from digital infrastructure entirely. It depends on whether breakthrough technologies we haven't even heard of yet make current AI look primitive.

Smart leaders are building technology strategies that work whether change happens faster, slower, or in completely different directions than anyone anticipates.

Your Response: Plan for Multiple Futures

Effective leaders don't try to predict the future more accurately. They don’t need to be certain all the time. They have no pent-up desire to get it right.

Instead, they see past the skinny black line and prepare for uncertainty systematically. Instead of drawing single lines through complex data, they map multiple scenarios and build capabilities that work across different possibilities.

Rather than betting everything on one forecast, consider how uncertainty might resolve in fundamentally different ways. I think about four distinct types of scenarios that capture the range of possibilities most institutions face:

Here's what each might look like for the demographic cliff:

The preferred scenario: Your reputation strengthens through focused excellence. Alumni networks actively recruit students. Employer partnerships create direct career pathways. You become known for specific outcomes people value. And while competitors struggle with declining enrollment, you develop waiting lists.

The managed decline: Enrollment drops 20% over five years. You strategically eliminate underperforming programs, right-size operations, and maintain quality with fewer students. It's challenging but manageable. You emerge smaller but financially sustainable, weathering whatever controversy might unfold in the process.

The pivot opportunity: Unexpected factors create new demand. Remote work enables national recruitment regardless of location. Employers emphasize demonstrated skills over institutional prestige. Economic disruption drives adult learners back to education. Your career services and flexible programs become competitive advantages.

The complete disruption: AI eliminates job categories while creating massive retraining demand. Major employers relocate to your region. Federal policy creates new funding streams. Global events make local education suddenly attractive. Your specialized expertise becomes essential.

Each scenario demands different capabilities today. Preparing only for managed decline means missing opportunities hidden in other possibilities. Ignoring disruption means getting blindsided by rapid change.

Building Adaptive Capacity

This approach requires three fundamental shifts in your thinking:

From prediction to preparation. Instead of forecasting which future will emerge, invest in capabilities that create value across multiple scenarios. Develop academic programs that serve both traditional students and working adults through modular, stackable credentials. Build technology infrastructure that enhances learning whether delivered online, in-person, or in hybrid formats. Create financial models with multiple revenue streams that function regardless of state funding levels.

From planning to sensing. Establish systematic methods for detecting early signals about which scenarios are emerging. Institute quarterly conversations with regional employers about skill needs and hiring patterns. Survey students every semester about program satisfaction and career preparation. Monitor competitor moves, policy developments, and technology adoption rates. Build decision-making processes that can rapidly incorporate new information and adjust course.

From optimization to optionality. Rather than perfecting single approaches, maintain multiple strategic options that can be scaled based on changing conditions. Develop partnerships that provide stability during enrollment declines and growth opportunities during expansions. Create program portfolios that can expand popular offerings while phasing out declining ones. Build revenue diversification that reduces dependence on any single funding source.

How to Turn Uncertainty into Your Superpower

I know. All of this sounds great in theory, but what about that knot in your stomach? You're still going to find yourself in meetings where everyone's staring at you, waiting for a definitive answer.

Here's how to turn uncertainty into your superpower:

When your board asks for five-year enrollment projections, don't give them a single number. Give them a range with a story. "We're seeing three possible paths here. If current trends hold, we're looking at a 15% decline. But if families start choosing local options over distant schools—which we're already seeing early signs of—that number could be closer to 5%. And if we nail our new employer partnerships, we might actually see growth."

When budget discussions get heated about exact targets, shift the conversation. "Let's build a budget that works if state funding drops another 10%, breaks even if it stays flat, and has room to invest if that new federal grant comes through."

And that knot in your stomach? It doesn't go away completely. But it transforms from the sharp panic of pretending you know everything into something more manageable—the steady awareness that you're prepared for whatever comes.

This isn't about giving up on planning. Max Mayfield didn't stop forecasting hurricanes when he started focusing on the cone. He just changed how people thought about his forecasts. Instead of false precision, he offered honest possibilities. Instead of one prediction, he showed multiple paths forward.

The future will always be uncertain. But that doesn't leave you powerless. It just means you need to prepare for the whole cone, not just the skinny black line running through the middle.